Broadway’s Roaring Twenties came to a roaring close with the rise of Hollywood’s “talkies” and the fall of the stock market. The subsequent exodus of talent posed a serious challenge for stage musicals. In 1929, Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern were among the first theater composers to venture into film. A year later, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart followed. Most writers eventually returned to the stage but not all of them. In 1932, composer Harry Warren was paired with lyricist Al Dubin for his first Warner Bros. film, which was so successful that he continued to write primarily for the screen.

The opulent “girls and gags” vaudeville-style revues such as Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies were among the first theatrical casualties, replaced by the more intimate Music Box-style revues championed by director-choreographer Hassard Short, who helmed the Fred & Adele Astaire vehicle The Band Wagon (1931), written by George S. Kaufman with Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz, and Moss Hart and Irving Berlin’s topical As Thousands Cheer (1933), featuring Marilyn Miller and Ethel Waters.

As the Depression deepened, New York’s Palace Theatre, the pinnacle of vaudeville, was rebranded the RKO Palace and converted into a cinema in 1933. Many feared that Broadway venues would follow, especially after the Shuberts declared bankruptcy that same year. However, instead of leaving show business, Lee Shubert used his personal savings to buy back his company’s theaters (at a fraction of their value) and then spent millions more to produce shows in those theaters.

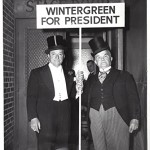

Historian Stanley Green noted that musical theater found one way forward when its creators “discovered that a song lyric, a tune, a wisecrack, a bit of comic business, a dance routine could say things with even more effectiveness than many a serious-minded drama.” The first musical satire was Of Thee I Sing (1931), by George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind with George & Ira Gershwin, featuring the comedy team of William Gaxton and Victor Moore on a presidential campaign trail. It became the first musical to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Another way forward was escapist entertainment, a speciality of Cole Porter, who came to notice with the urbane and titillating Paris (1928), featuring the hits “Let’s Misbehave” and “Let’s Do It.” His greatest score of this period, though, was Anything Goes (1934), which Porter himself considered one of his two perfect shows (the other being Kiss Me, Kate in 1948). It was the first of five shows Porter wrote for Ethel Merman, who secured her standing as First Lady of musicals with her boundless energy in such songs as “You’re the Top.”

As political tensions rose in Europe, many artists came to America. One of the few to land on Broadway was Kurt Weill, who had recently parted company with Bertolt Brecht. His 1933 Broadway debut, The Threepenny Opera, closed after only 12 performances. The show had better luck 20 years later, when composer Marc Blitzstein’s revision saw a record-breaking run Off-Broadway. Weill found his most productive American partnership with Maxwell Anderson, the first of their four collaborations being the musical satire Knickerbocker Holiday (1938), starring Walter Huston.

Marc Blitzstein’s own Brechtian musical was The Cradle Will Rock (1938), directed by Orson Welles, which was shut down a few days before it was to begin performances, presumably censored because its pro-union plot was too radical. Welles, producer John Houseman, and Blitzstein rented another theater, and the audience walked 21 blocks from the original venue to the new space. Since the orchestra refused to play, Blitzstein performed the entire show at the piano, joined by actors singing from the audience.

As radio began offering more variety entertainment, intimate revues eventually saw their audiences diminish. Still, the two most popular musicals of the decade were Pins and Needles (1937) and Hellzapoppin (1938), which exemplified the two ways forward in the 1930s. The first, produced by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, was a topical, pro-union piece that ran for 1,108 performances. The second, produced by vaudevillians Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson, was a “greatest hits,” audience-participation evening that ran 1,404 performances.

Rodgers and Hart returned from a disappointing jaunt in Hollywood to write a string of successful Broadway shows with producer-director-librettist George Abbott, including On Your Toes (1936), Babes in Arms (1937), The Boys from Syracuse (1938), and Pal Joey (1940), starring Vivienne Segal and Gene Kelly. The fast-paced staging and naturalistic comic dialogue, as well as the sexual frankness and anti-hero leading roles, of these shows set a model for musical comedy that was used for the next 50 years.

To sample the sound of Broadway music in the 1930s, explore “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” (listen here) by Jay Gorney & Yip Harburg from the revue Americana (1926); “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” (listen here) by Kern & Harbach from Roberta (1933); “You’re the Top” (watch here) by Cole Porter from Anything Goes (1934); “September Song” (watch here) from Weill & Anderson Knickerbocker Holiday (1938); and “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” (listen here) by Rodgers & Hart from Pal Joey (1940).