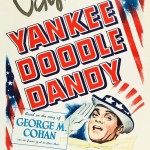

“There’s little that’s really original,” Roger Ebert has said of the musical biopic Yankee Doodle Dandy. “The greatness of the film resides entirely in the Cagney performance.” In its 1942 review, Variety similarly noted, “James Cagney does a Cohan of which the original George M. might well be proud.” Indeed, after seeing the film, Cohan’s first response was, “My God, what an act to follow!”

“There’s little that’s really original,” Roger Ebert has said of the musical biopic Yankee Doodle Dandy. “The greatness of the film resides entirely in the Cagney performance.” In its 1942 review, Variety similarly noted, “James Cagney does a Cohan of which the original George M. might well be proud.” Indeed, after seeing the film, Cohan’s first response was, “My God, what an act to follow!”

James Cagney was best known for his 1930s gangster roles in film, but he began his career in vaudeville as a dancer and comedian. He had disliked Cohan since 1919, when Cohan sided against an Actors’ Equity strike, but Cagney took the role partly because he believed that starring in such a patriotic film would deflect recent political criticism about him. In 1940, Cagney had been among 15 Hollywood figures named in John R. Leech’s testimony before the HUAC.

The film, written by Robert Buckner and Edmund Joseph (with uncredited work by Julius and Philip Epstein), is presented as an implausible flashback. Cohan is summoned to the White House to receive a congressional medal, and FDR recalls seeing him perform some 40 years earlier. “I was a pretty cocky kid in those days,” Cohan says, then starts narrating his life story for the president.

Cohan objected to the liberties taken with some facts, specifically the creation of the character Mary (played by Joan Leslie), a composite of his two wives (Ethel and Agnes). Producer Hal B. Wallis dismissed Cohan’s concerns by replying, “The deep-dyed Americanism of your life is a much greater theme.” Ethel later sued for violation of her “rights of privacy,” but Judge William Bondy ruled, “The introduction of fictional characters and a large fictional treatment of Cohan’s life may hurt Miss Levey’s feelings but they do not violate her rights of privacy.”

The sets, costumes, and dance routines, though, are faithful to the originals and provide a glimpse of the American musical theater at the turn of the 20th century. Cagney’s performance is directly styled after Cohan’s unique mannerisms, supervised by dance instructor John “Jack” Boyle, who had performed in The Cohan Revue of 1916, and by technical advisor William Collier, who had costarred with Cohan in the 1914 revue Hello, Broadway.

Cohan was also a consultant on the film, but his failing health only allowed limited involvement. His contract also stipulated he compose three new songs, but he was too ill to write them. In fact, the studio worked to complete production before Cohan died, moving up the New York gala opening from July 4 to May 29.

In line with the film’s patriotic theme, Warner sold tickets for the premiere only to those who had bought war bonds from $25 to $25,000, which raised more than $5 million for the war effort. Reviews the next day were excellent. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther thought it “as affectionate, if not as accurate, a film biography as has ever — yes, ever — been made,” and Harrison’s Reports called it “one of the most sparkling and delightful musical pictures that have ever been brought to the screen.” Cohan died six months later.

The movie was one of Film Daily’s Top 10 of 1943 and received eight Oscar nominations, including picture, director (Michael Curtiz), original story (Buckner), actor (Cagney), supporting actor (Walter Huston), editing (George Amy), sound recording (Nathan Levinson), and scoring (Ray Heindorf and Heinz Roemheld). It picked up wins for Cagney, the first for a leading musical role, as well as sound and score. Cagney recreated his role for a scene in the 1955 film The Seven Little Foys. In 1993, Yankee Doodle Dandy was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress National Film Registry.

There was a 1942 half-hour CBS radio adaptation for the Screen Guild Players, with original stars Cagney, Leslie, and Huston. The film hasn’t had a stage adaptation, but the 1968 musical George M! (by Michael Stewart and John & Francine Pascal) and 2004 musical Yankee Doodle Dandy! (by David Armstrong and Albert Evans) both use Cohan’s music to tell his life story.

Listen to the soundtrack, then rent or purchase the film through Amazon Prime. TCM also regularly broadcasts the film on July 4 and will again this year. For more about the making of the film, read the 1981 Wisconsin Press edition of the screenplay, edited by Patrick McGilligan.

NEXT, explore the musical biopic Stormy Weather (1943), loosely based on the life of its star, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Among the 20 (yes, 20) musical numbers in the film’s 80 minutes (yes, only 80) are “Jumpin’ Jive” (with Cab Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers), “Ain’t Misbehavin’” (with Fats Waller), and the classic title song by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler (with Lena Horne and Katherine Dunham).

THEN, look for Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), music by Saul Chaplin and Gene de Paul with lyrics by Johnny Mercer, set in the 19th century Oregon Territory. Its barn-raising sequence is among the best dance sequences ever filmed.