In Broadway’s Golden Age, producers would hold backers’ auditions to raise funds. For example, librettist Arthur Laurents remembered how Cheryl Crawford organized an event for West Side Story investors at “an apartment on the East Side [where] there was no air conditioning and you could hear the tugboats. She didn’t raise one penny.” If repeated auditions proved unsuccessful, some producers resorted to making cold calls from the phonebook, as lampooned in The Producers

, until lawmakers intervened.

Today, such “angels” tend to be “accredited” investors of significant net worth. As defined in Rule 501 of Regulation D of the Securities Act of 1933, this means someone worth over $1 million or who has earned over $200,000 for the past two years. The presumption is that such individuals are financially sophisticated – they know that about three-quarters of all shows don’t recoup their investments – and they can afford to take a $50,000 tax write-off.

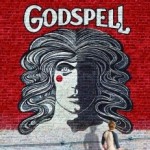

The New York Times reported on a new model, new at least for commercial theater. The recent Broadway revival of Godspell

The New York Times reported on a new model, new at least for commercial theater. The recent Broadway revival of Godspell received more than half of its $5 million capitalization through crowd-funding from a group of about 700 investors, who donated as little as $1,000 each. In return, shareholders get regular e-mail updates, webinars, discount offers, and more. Lead producer Ken Davenport said he was inspired by the success of Obama’s 2008 campaign and by Kickstarter. Launched in 2009, the crowd-funding website has made significant progress in the past two years. In 2011, there were 50,144 backers who pledged $4,051,962.62 through Kickstarter for 931 theater projects that cost from $1,000 to $50,000.

In tandem with widening investor participation, Godspell has also taken a cue from nonprofit theaters and offered an 11-week talkback series this winter, aired on Sirius XM On Broadway channel. If Davenport is successful in recouping the show’s investment, expect to see more of his hybrid model.